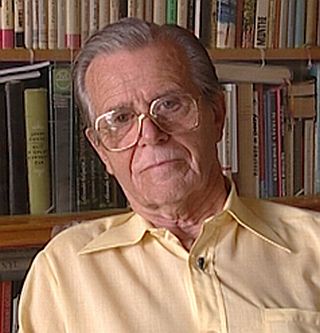

Zoltán Kukula (1926)

Biography

“I am not angry with the people, because I take life as it comes. Maybe that’s why I don’t long for revenge, although I cannot forget it.”

Zoltán Kukula was born on April 13, 1926, in Želiezovce. As a child he lived in Banská Štiavnica and he still loves this quaint town. After gaining the primary education at a public school, he moved to Bratislava to live with his father who was ordered directly by a minister to bring up his son Zoltán. In Bratislava he attended a state grammar school, where he successfully passed leaving examination in 1945. In the same year he was arrested and imprisoned along with his father, the Chief Executive Officer in the Ministry of Finance. Young Zoltán Kukula was released from the prison after two weeks and he continued his studies at a university. In 1948 he was arrested again due to plucking off a campaign poster and, as a result, he spent two weeks in custody. Then he started to work as a physical education teacher in Bánovce nad Bebravou and a year later he moved to Poprad, where he laid foundations of basketball competition. On October 28, 1952, he was called to the District National Committee and subsequently he was investigated because of the letter he received from his friend called Nemec. As a result, he was falsely accused of high treason, subverting of the Republic as well as of a membership in the White Legion resistance movement. For two long months his wife had no idea what had happened to her husband and why and where he had disappeared. Meanwhile, Zoltán Kukula was investigated and battered severely. Later he was transported to the prisons in Levoča and Košice. Due to lack of evidence he was finally released, but he still had to face unpleasant consequences of his imprisonment including the loss of his favourite job as well as some of his friends’ abandonment. Although he suffered a lot, he does not long for the revenge. His only wish is to never let the cruel and inhuman communist regime reign again in the future.

“Listen to the Radio Free Europe…”

“Nemec worked here only for a year, but I really liked him, because he was open-minded and friendly. He taught at a business school in Trenčín later and he was also sent there to help with the management of the school. The students liked him, too. However, they later denied it. He moved to Trenčín, because he didn’t get a flat here. A school caretaker called Antalová made a deal with Libant and sent him all the letters Nemec wrote to me by a bus driver to Dobšiná. Once Nemec wrote me: ‘Zolo, listen to the Radio Free Europe, you’ll laugh at it.’ This letter was a reason for my apprehension. As a result, I was accused of an active membership in the White Legion resistance movement, of the high treason and subverting of the Republic. Moreover, I was accused of undermining of the Youth Association, etc.”

“I Really Cannot Imagine a Better State”

“Now I’ll come back to talking about the first Slovak State. I really cannot imagine a better state. It was small, but the Germans took it under their wings and they protected it. People used to say the Germans had claimed that if we stood on their side, we would have a good life. Especially in political matters nobody could do anything against such a strong power as Germany was. In the Slovak State, there we had the things which you couldn’t have found anywhere in the Europe then: Swiss chocolate and English fabric. Shops were loaded with goods we’d never seen before.”

“I Hate the Communists and the Communism”

“Well, I was asked: ‘What is your attitude towards the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ)?’ I answered: ‘I hate the communists and the communisms especially after the year of 1948, because the incompetent people have come to power.’ Then I really don’t know how I found myself laying in pain on paillasse on the ground in an infirmary. In the morning one of the wardens, who was very kind asked me: ‘Who battered you so hard?’ Then he swore at those who did it to me. I suffered broken teeth, I had a black eye and unfortunately my left kidney was damaged. I’ve got a medical record. That’s why I was given a card of the handicapped, but I was really ashamed to take it and I still try to walk and work normally.”

Humaneness of Wardens in Inhuman Conditions

“Once when I shared a cell with Laci Šterbinský we heard the dinner was coming, because some prisoners were carrying pots and they started to ladle up food. We had to push our plates outside by our legs and I still remember that they ladled up beans and a slice of bread. Well, a lot of little stones were in the food, because they usually didn’t clean the ingredients before cooking in the prison. When we finished our food, the warden opened the cell and said: ‘Boys, do you want another portion? There is some food left.’ We agreed and suddenly Laci started to skip. The warden asked him: ‘Why are you skipping?’ ‘Because I'm trying to make more space in my stomach for the food,’ he answered. The warden smiled and gave us the food. But after a while he started to shout at us: ‘Why are you bothering me?’ We really didn’t understand what was going on. After a while he opened the cell and told us: ‘Those bastards came here to investigate.’ Then we understood that some of the wardens were human and they did not lose their humaneness in spite of the jobs they had. We understood that they were watched and they were afraid of their supervisors, too.”

Father-in-Law’s Execution

“My wife’s father was abducted to Russia. My wife always says he was abducted by the Russians, but the Russians were only executors. The tragedy is that our people were those who sold out their own fellow citizens to the Russians. Even in Veľká some of the betrayers are still alive. His best friend betrayed him, because my wife’s father was a chairman of the Hlinka’s Slovak People’s Party (HSĽS) and his best friend was a passionate guardsman. Since he wanted to save himself, he betrayed my wife’s father. Consequently, he was taken to Russia. When two men came back from there, one of them was called Hlásny, firstly they didn’t say a word, but later, after some period of time, they told us the father was still alive waving with his hand when a bulldozer was pouring soil on him burying him alive. People told me he was a very good man. He worked in sawmill and when the bridge to Veľká exploded, he offered people boards for free to cover their broken windows, because they didn’t have glass. People called him Miško; they always say he was very helpful. He never did anything bad to anybody in his life.”

The story and videoclips of this witness were put together and published thanks to the financial support of EU within the programme Europe for Citizens – Active European Remembrance.