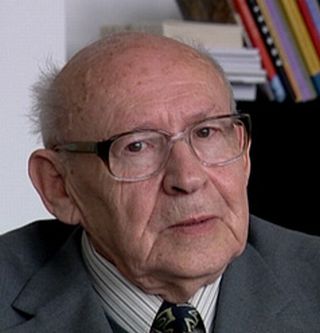

Marián Kolník (1928 - 2019)

Biography

“It all had only one purpose - to show us that we could love more and to make us better.”

Marián Kolník was born on December 11, 1928 in Hrachovište in a peasant family of a Catholic bent. He attended the public school in Hrachovište and then he studied at the municipal school in Krajné for three years. After the war in the year 1945, he started to study at the Grammar School in Nové Mesto nad Váhom where he also passed the leaving examination in 1949. Later he enrolled at the Faculty of Theology in Nitra and became a novice. In May 1950, as a consequence of the Action “K” when the state authorities abolished also the rest of orders, he ended up in the Monastery of Redemptorists in Kostolná near Trenčín. Then he was transferred to Púchov to the dam called Priehrada mládeže (Youth Dam) and subsequently he was interned in Pezinok monastery with the prison regime. He was sent to the military labour camp in Libava on September 23, 1950. In the same year at the beginning of October, he was transported to the Auxiliary Technical Battalion (PTP) where he spent forty months. He was definitely released on December 31, 1953. Until the year 1957 he had worked in Hydrostav in Trenčín as a concrete layer and as auxiliary technical worker. Later he got employed in Hydrostav in Bratislava. In the 1960’s he got married and after finishing his studies at the Faculty of Economics in Bratislava he graduated and became a civil engineer. In the 90’s he was elected a chairman of the Christian Democratic Movement (KDH) in Nové Mesto nad Váhom. Marián Kolník died on October 31, 2019.

Trench Work and Transition of Russian Armies

“When I finished the fourth year of municipal school, Germans recruited men to built trenches because it was necessary to entrench our cities. For example, Čachtice town was a kind of gateway to the region of Považie towards Piešťany, so it was necessary to dig various trenches and anti-tank ditches there and they were quite wide and deep as well. And everyone who went there got some money. Since we were many children, it was good to earn some extra money. We got “Arbeitskarte” – it was a kind of work permit that enabled us to travel every day from Hrachovište to Čachtice. It was about seven kilometres away when we went by train. And people who had taken the charge of building of those anti-tank ditches and various trenches awaited us there. They had precise schemes, you know, at that time Germans had it all very well organized. And I worked there with a team of gypsies or sometimes with white men. I was working there also in winter, but on Easter in the year 1945 Russians were so close to our country that it didn’t make sense to go digging trenches anymore. Thus I stayed at home. It was exactly on Easter Monday when Russian armies came and took over the village of Hrachovište. It was a difficult situation when those Russian armies were crossing our land because it was necessary to protect our families somehow. Behind our house there was something like backyard or rather garden oriented to the wood and with our father we had dug some bunker there, we had covered it with balks or rough boards and brought some food there. And when Russian armies were moving across Hrachovište, we stayed there.”

Military Labour Camp in Libava

“On September 23, 1950, I was transported to Libava. It was a military labour camp. Probably we could say it was a drill field. It was a large area about 1200 square kilometres where training of professional soldiers took place and where they tested various kinds of gunfire. I remember that after spending a month in Libava we started to make the rounds of neighbouring villages that remained empty because Germans had left them and we took the rest of straw from barns. We needed it as a filling of straw mattresses for soldiers. All the towers were destroyed there, I saw them and it meant that soldiers used to aim their cannons accurately at those towers and this way they trained firing. In other words, it was a real military drill field. It was a bit surprising for me that right after coming there in the morning they gave me some blanket and the man who took charge of it gave me also some clothes and other things such as boots, fatigues and I think some walking clothes as well regardless of whether it fitted me or not. Later we had to interchange those things. I wasn’t there alone. At that time there were about fifty or sixty men concentrated in the camp and as to say about my first work - I got a wagon and one horse and together with one boy from Prague we went to bring the straw to mattresses. The village was called Strelná and I was ordered to go there with him. Name of the boy was Janko, Honza. Well, it was my first job in Auxiliary Technical Battalion (PTP) in Libava. Later, when everything was arranged and when they assigned us to individual houses that Germans had left there, we had some marching drills occasionally; however, it wasn’t as harsh as we had initially thought about military training.”

False Telegram about Mother’s Death

“I can recall a really strange situation. It was on Sunday sometime at the end of October, it was still nice and sunny weather. Someone from the office shouted: ‘Soldier Kolník, come to the office!’ So I returned and duty officer gave me the telegram: ‘Your mother died. Find some walking clothes and go, attend the funeral.’ And the funeral should have taken place on the next day, on Sunday in October sometime at about four or five o’clock. Express train from Pilsen went at about ten in the evening. I talk about it just because it was really strange situation. The telegram strayed for a while. When I opened it, the name Ján was written there but I am Marián. ‘Ján Kolník’ – it said. I agreed with that officer that as it was announced by telephone operators who surely weren’t very responsible, they must have misheard the first part of my name, so this way Marián resulted to Ján. Then - all right. When I came to Nové Mesto nad Váhom, I asked some man who was working at the station how it happened that my mother died so suddenly. And he responded: ‘Oh man, your mother is alive, she didn’t die.’ ‘Look here, I have got a telegram!’ ‘It must be mistaken.’ I ambulated there back and forth, when I suddenly saw my mother with a basket on her back, you know, women in the village usually carried it, and at that moment I thought I saw an apparition. I couldn’t believe my eyes; I thought I was dreaming or something like that. But it was really my mother. I said: ‘Mother, I am here to attend your funeral!’ Later the situation was clarified. There was a boy in Pilsen who came from Hrachovište and his name was Ján Kolník. So I attended the funeral of his mother and then we announced him that there was a mistake and the telegram had probably strayed for a while in military quarters in Pilsen. We explained him that the letter was sent to me instead of him.”

Transfer to Pilsen – Building of the Tank Training Areas

“We only waited what would happen with us. And then at the beginning of October we suddenly got an order that we all had to move to Pilsen where we also should undergo the basic military training exercise. We were a bit naive because we thought we would train with guns there but it had never happened. In Pilsen we were supposed to build the tank training areas what were huge military quarters where tanks were stored, I mean some garages for tanks but there was also a large tank barrack. I worked with a group of bricklayers. We usually carted bricks or mortar and we passed it to bricklayers and the like. Bricklayers were civilians and we as the members of the PTP assisted them.”

Positive Approach to Past Situations

“On one hand it was in contrast to all human rights and morals as well because they forced us to do various works regardless of whether we understood them or not, you know, we weren’t specialists, so we were in danger and we lost many years of our professional lives there. On the other hand it was really nice that it didn’t work out as the communist authorities had planned it. I mean we were locked in those monasteries and we prayed and meditated more than ever before. And in spite of all the hard work we proved that we were decent people and we could and wanted to work and we could talk to others. And in my opinion it was the nicest and the most fruitful apostolate we could ever do. I don’t want to speak highly of the PTP, it is not my intention; I would rather say that in spite of all those trials and ordeals that we had to undergo there and that were in contrast to human rights and justice, God in his infinite wisdom managed to show us that if we took the faith seriously, we became those lights in the mine or at any place where we had to work.”

Seizure of the Premises of the Zobor Monastery

“The Divine Word novitiate was held in Zobor monastery which was about two kilometres away from Nitra town on the hill. It was the Society of the Divine Word monastery where missionaries educated novices. So simply said, at night at about four or three o’clock a group of policemen, members of the State Security Corps, took over the monastery. I think there were also a lot of workers with guns who belonged to the people’s militia. They broke and entered the building, ran and shouted in the corridors: ‘Get dressed and take only the most important things!’ and the like. We somehow suspected these events and priests were so clever that they had previously sent the youngest boys from the fourth grade home. We were almost about to take the leaving examination, so we stayed there with theologians from higher grades. And as people usually describe their action in other situations, they did it in the same way. They changed nothing, they were absolutely dull. They had learned schemes of how to break into the monastery from more sides and how to make a noise with automatics in their hands and things like that. They thrust us into buses and we left. Well, in the morning we arrived to Kostolná village. Then we had to stay there, you know, they had a month-long practise, so they accommodated us there somehow.”

Living at Liberty

“I was definitely released on December 31, 1953. When I was leaving Karviná, they allowed me to take my civilian clothing. However, for example father Porubčan didn’t have it, so we went to Ostrava and bought an old duffel coat for him. He was wearing this kind of coat for the first time in his entire life. We went home and he was, I don’t want to say timorous, he merely followed the military rules and we were told to report to some enterprise within five days after finishing the military service. During the way I mentioned to Jožko Porubčan that I had a brother in law who worked in Hydrostav in Trenčín where hydroelectric power station was being built at that time and I proposed to ask him about job opportunities for both of us. And it really came true. When I arrived home on the New Year’s Day, I went to see my brother in law and I told him: ‘Look,’ his name was Jozef and he worked as a taskmaster in that enterprise, ‘I have got one friend here, his name is Jožko Porubčan and we would be grateful if you could find some job for us.’ And they really invited us to come there within those five days. I got to a Hungarian team that concreted blocks of the hydroelectric power station and Jožko got to the stone pit.”

The story and videoclips of this witness were put together and published thanks to the financial support of EU within the programme Europe for Citizens – Active European Remembrance.